Tags

arizona, grand-canyon, hiking, national-parks, short stories, short story, story writing, travel

It’s Sunday, so here is a story. I’m trying to write 52 bad short stories this year. 2 down, 50 to go!

The Grand Canyon Conspiracy

The late afternoon sun was sinking into the Arizona horizon. The living room dark, except for the glow of the computer monitor on the corner desk.

“A person could go blind staring at that screen in the dark.” Joe Mason walked into the living room and switched on a lamp in the opposite corner. His thirteen-year-old grandson, pounding on the keyboard in front of him, did not look up. “Dalton, what are you up to?”

“Homework – a report on my virtual visit to the Grand Canyon. It’s due next Tuesday.”

“What all do you have to do?”

“Just visit and write 500 words on what I saw and how the National Parks Service could make the park better.” Dalton pointed to the monitor where the Grand Canyon filled the screen in front of him. “Mom said that you actually went there once, before they put up the wall and made it a virtual park.”

“Yes, my parents took me there when I was about your age.”

“Wow, wasn’t it scary, I mean, there wasn’t a wall. Couldn’t you just fall in?”

“Actually, it was quite beautiful. The cameras online don’t do it justice.”

“What was it like?”

“Well, close your eyes. Now, picture yourself standing at an edge, almost like the high dive at the YMCA, except you can’t see the water below you. The breeze is gentle, but it’s behind you, nudging you closer to the drop off. The wind smells of dryness, the fragrance of desert drought, kind of sweet, kind of acidic. You can barely hear the river running way down beneath your feet; it sounds like just a gentle trickle, not the mighty river that carved a canyon.”

“Cool.” Dalton opened his eyes and stared at the image on the screen as his grandfather continued.

“Well, the funny thing is that gravity seems stronger at the edge of the canyon. It’s like it’s trying to pull you in, to fill the void. An irresistible pull, you must think about stepping back away from the rim. At the same time, I always wanted to jump; it felt like I could fly across.”

“That is so dangerous! No wonder the government walled it up and closed it to the public. People probably jumped off all the time! I can imagine the blood-spattered rocks!”

“There was a huge uproar when the Parks Service did that. It took away our rights to see the canyon, to experience it in person. I still think there has to be a better way to keep people safe than to close the park.”

“But safety is the ultimate good, isn’t it Grandpa?”

Joe cringed to hear his grandson parrot the current political mantra. Alarming things had been happening lately, all in the name of safety.

Dalton looked at his grandfather, and then returned his gaze to the screen, watching the crescent moon rise over the east rim of the canyon from one of the camera views. He stared at the picture with his forehead shriveling into a frown. “Hey, something’s wrong with the camera system.”

“What do you mean?

“Look at the moon.”

“Yeah, so, there’s a moon. It’s getting dark there. We’re only 90 miles away. It’s getting dark here, too.”

“But outside our window the moon is in the nearly full. Ninety miles away at the canyon, it’s the first quarter.”

This got Joe’s attention. He squinted at the monitor, looking for other time cues. “The wind is too gusty, too. Look at the dust fly.”

“I don’t think this is real time anymore,” said Dalton, “but the site says it’s supposed to be.”

“I think somebody is hiding something.”

“Oh, Grandpa, you always think the government is up to something.”

“Well, it’s Friday night and we’re only an hour and a half away. Message your mom and ask if you can go for a ride with me. Tell her we’ll be back in about four hours.”

Twenty minutes later, they were sitting in Joe’s pickup, drinking Cokes and eating pemmican from the local reservation. While Joe drove, his mind was churning away with the possibility of another conspiracy for his underground newsletter. His readers would eat this one up. They were starting to get bored with the same old conspiracies. The most famous argument, whether Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, was in its ninetieth year now.

Time passed quickly as they made the drive from Prescott, Arizona, to the site of the old Grand Canyon National Park. Joe drove up to the gate and Dalton groaned upon seeing the locked gates. Joe just snickered, as he got out of the truck and retrieved some bolt cutters out of the back toolbox. By the light of his headlights, he cut the rusty lock and opened the gate.

“Grandpa, we’re breaking in! We can get in big trouble!”

“Nonsense, this is public land. I’m the public. I want to visit my land.”

“We could go to jail!” Dalton was panicking now. “A life of crime would seriously interfere with my plans to write the next great virtual game. Prison inmates don’t get very powerful computers.”

“Oh, just be quiet. I’m the adult, I’ll get in trouble. You’ll just go back to school with a great story to tell about how the Federal Government shot your grandfather for reporting their latest antics. Now look up there, that’s your wall of safety.”

They drove to the end of the neglected park road to a nine-foot brick and stone wall. It seemed to extend endlessly in both directions. Mounted on top of the wall, about every 50 feet or so, were digital cameras. Joe and Dalton got out of the truck and turned on their flashlights.

“Look,” Joe said, “The cameras are broken. There’s glass from the lenses of this one on the ground.”

“Yeah, this technology is at least twenty years old. It’s not even compatible with the current systems.” Dalton, like most eighth-grade boys, fancied himself a computer expert.

“Let’s walk a bit,” said Joe.

“Where?”

“Let’s see where the wall goes. It can’t block off the whole canyon.” The two of them trekked, shining flashlights at the wall and the open desert around them.

About an hour later, Joe thought he could make out a break in the wall. In ten minutes, they were standing at a crumbled portion of brick, peering over at the canyon.

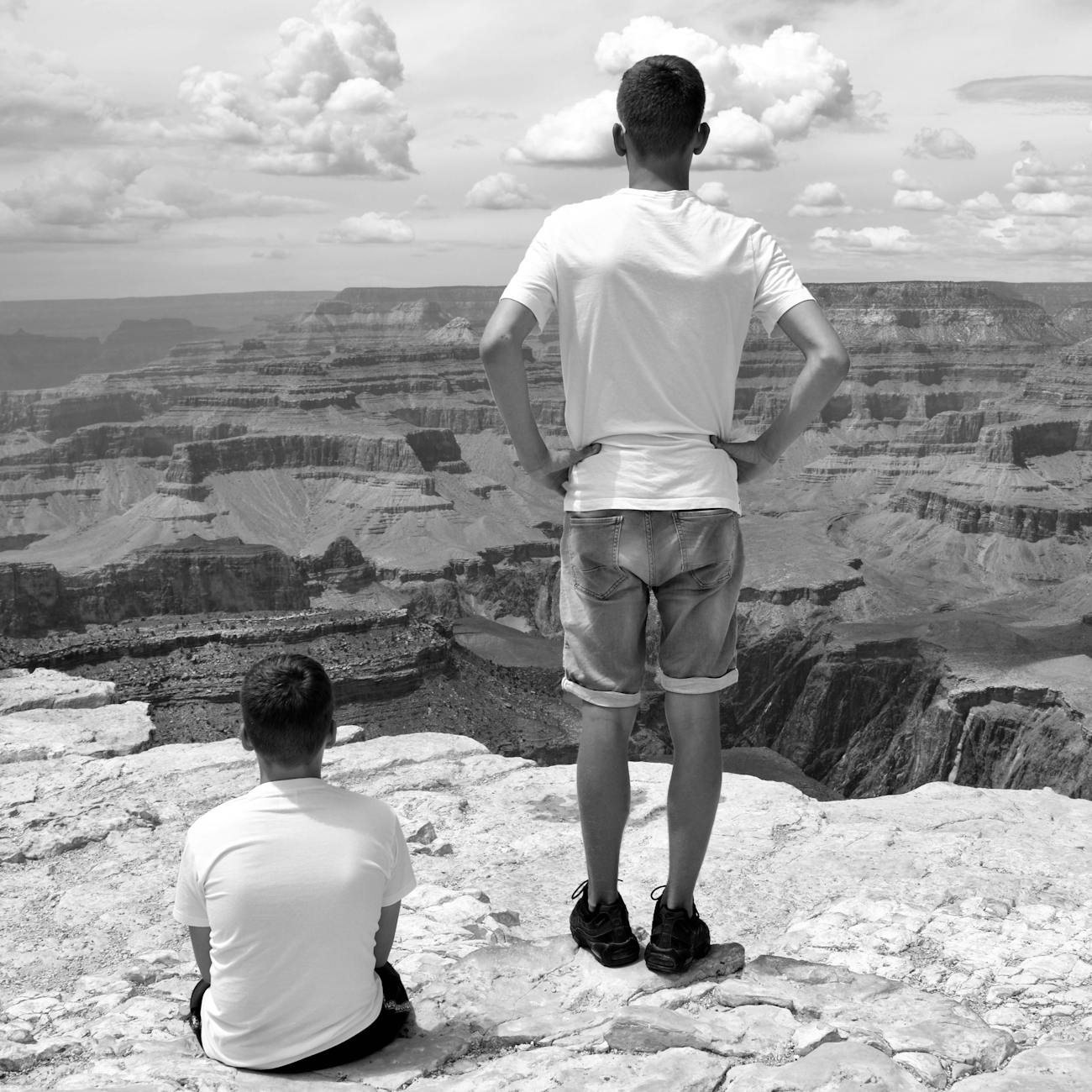

“Well, you wanted to know what it was like to really see the canyon. Here’s your chance,” Joe said as he stepped over the bricks. There was a ledge of about 8 feet between the wall and the rim of the canyon. From where he stood, Joe could look across and see a similar wall lining the opposite rim of the canyon. Dalton followed him through the hole in the wall. They stood on the path and stared.

The canyon sides almost glowed in the light of the nearly full moon. It was just how Grandpa Joe had described it, except it was more beautiful and more mysterious and the gravity felt strong. Dalton crept to the very end of the edge. He looked down and could see the Colorado River, a silver ribbon winding along the bottom. The cameras never showed this view.

“I wonder,” said Dalton, “what other things we’re missing because we see it all online and no one visits anywhere for real anymore.”

There was a faint mechanical growl coming from the west. Joe motioned for Dalton to follow him and they picked their way along the narrow path. They walked in silence, trying to absorb the sights and smells of the place, when Joe stopped abruptly.

“What is it, Grandpa?”

“I was wondering how they paid for all of this wall and camera stuff,” Joe said.

Dalton pushed past to see what he was talking about. The breeze was now in their faces and the odor in the air was oddly familiar. There was a glow in the sky that didn’t come from the moon, and it took him a moment to realize that the aura was from manmade lighting. Half a mile from them, a semi-circle of industrial work lights illuminated a work area. Bulldozers were pushing huge piles into the canyon. Part of the canyon, on the other side of the work area, seemed to be missing. Joe had a bad feeling about this. They were walking again, trying to get close enough to identify substance in the piles. A truck pulled up nest to one of the bulldozers and although the smell told them everything, Dalton read aloud the name on the side of the truck:

“State of California Sanitation Department.”